Mountain communities in Central Afghanistan experience a water crisis that is new. According to meteorological data, precipitation in provinces such as Bamyan and Daikundi has fallen dramatically. The overall result has been catastrophic. The drought of 2018 affected 26,200 families in Bamyan and Daikundi provinces. The drought has forced rural communities to travel for several hours on a donkey or on food for drinking water. Although the area experiences heavy rainstorm events, when they do occur it is followed by seasonal flooding and landslides. Reforestation will not solve the water governance issues in Afghanistan. However, implementation of integrated forest restoration in accordance with policies with community engagement is a critical component of climate resilience in the mountain region.

Despite weak governance, limited state capacity, and accelerating climatic stress, forest-based approaches remain one of the few viable pathways for long-term water security and climate resilience in Afghanistan. Unlike large-scale infrastructure projects that depend on political stability, external financing, and centralized control, reforestation and watershed restoration operate at local and ecological scales, where community stewardship and natural regeneration can still function under constraint. By restoring soil moisture, regulating runoff, and stabilizing fragile mountain hydrology, forest ecosystems offer a low-cost, adaptive response to drought that does not wait for ideal political conditions. In this context, forests are not a secondary environmental concern but a foundational strategy for survival in a climate-vulnerable and institutionally fragile state.

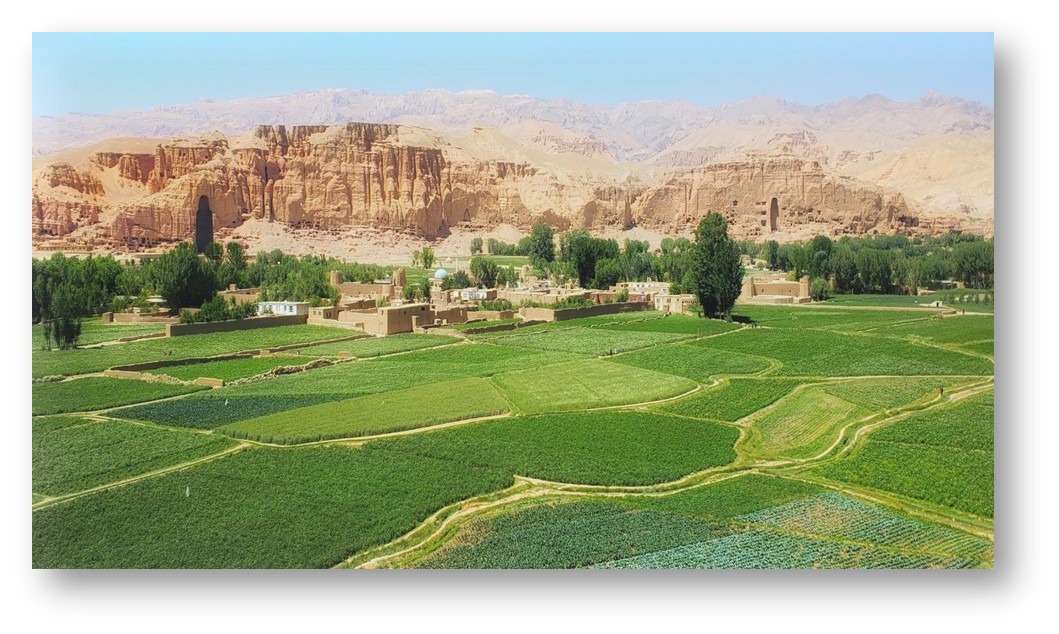

Central Afghanistan's Environmental and Climatic Context

In the Hindu Kush mountain range, central Afghanistan and the provinces of Bamyan and Daikundi are located at altitude of more than 2,000 m. The climatic condition of this area is that of a continental type which is associated with extreme variations between -40oC and 45oC,and also low-precipitations which are mainly influenced by winter snow and spring rainfall. The amount of precipitation received in the area was 400-1200 mm each year with the highest rate received in the period between January and April. It is important to note that current satellite data records alarming trends. The 2018 reading by NASA showed that the region received the lowest amount of snow since 2001, and this was predictive of a very severe drought in 2018-2019 resulting in mass migration out of rural regions. These mountainous areas have been denuded by the trends of deforestation in the past such as fuel-wood harvesting, conflicts and change of land use thus they have no forest cover to influence the natural hydrological processes.

How Reforestation Addresses Drought and Hydrological Extremes

Forests are also regulators of water resources because they have a number of hydrological functions. The rainfall received on forested land is collected by trees on which research evidence indicates that the conifers and broadleaf trees can intercept 4 to 6 mm of rainfall per event. This captured rainfall protects the soil against being rained upon and hence runoff and soil erosion.

At the same time, forests reduce surface run-offs during heavy rains, which causes flooding and landslides. This is because the precipitation is transformed to smaller streams which creep slowly in the forested soil. Consequently, forests minimize the velocity of flood and landslides on mountainous streams and riverbank surplus. This is attributed to the fact that forests cushion against floods and landslides, which are becoming common to the people in valleys and naked slopes to the south and western of Afghanistan. Globally, the watershed management studies on watersheds have shown that forested watersheds experience less runoff during floods compared to non-forested watersheds with relatively similar precipitation rates.

In the case of Central Afghanistan, re-afforestation of the Hindu Kush range would have serious impacts against degradation of hydrological processes which played a major role in the natural water cycle. Growth in these regions would have a considerable impact on the rainfall implications in the processes of the local atmospheric circulation as more moisture is recycled and the intensity of precipitations on such areas is higher because of lesser evaporation on the exposed rock and soil surfaces in these areas.

Challenges and Barriers to Forest-Based Water Security

The challenge of reforestation, which is a method implemented to adapt to climate change, is greatly faced by Afghanistan. This is because there is a lack of institutional capacity to ensure that forest protection and management approaches are implemented. Second, there are pressing and immediate livelihood factors that can make forest degradation an extremely attractive thing for rural communities. The rural communities of Bamyan and Daikundi rely on forest resources for energy construction as well as livestock fodder requirements. The drought effects and limiting economy make short-term livelihood pursuits more attractive than forest conservation

Third, climate change factors make succeeding at reforestation more difficult. The earlier snowmelt resulting from warming climate conditions indicates that water storage and infiltration processes will occur during periods when most settlements require less water while extending an already long dry summer season. The predicted decrease in annual precipitation in parts of Central Afghanistan indicates that, on its own, reforestation can no longer ensure water availability because forests in regions with low precipitation (arid to semi-arid) could fail to show positive correlations to increased water availability because higher evaporation losses occur.

A Pathway Forward

A forest-based water adaptation measure that achieves results on multiple fronts is imperative to succeed on a bigger scale in Afghanistan. The present policies and programs within Afghanistan, such as National Forest Management Policy, National Adaptation Programme of Action, and Climate Action Plan, identify forests as vital to adaptation to precipitation and glacier change. The challenge lies within limited funding and technical expertise to execute these programs.

One such opportunity is the realization of the reforestation programs at the global climate finance platforms. The REDD+ program, under the stewardship of the Green Climate Fund, is an economic incentive provided to the countries to reduce deforestation and augment carbon emissions. Afghanistan stands a chance in enjoying funding outcomes that can be found in REDD+ provided that they are in a position to demonstrate growth of forest areas and carbon sequestration within Hindu Kush mountain ranges and transfer such rewards to farmers as incentive to protect forests rather than immediate survival requirements that are considered in conserving forests.

Further, reforestation can and must be accomplished together with other water and land management interventions. Water retention landscapes consisting of terraces, swales, mini-check dams, and strategic ponding within reforestation programs can greatly speed up soil formation and water infiltration on very degraded land. These comprehensive landscape strategies, which worked successfully in semi-arid parts of Portugal and other regions within Africa’s Sahel belt, have shown they can restore hydrological function within 5-10 years, rather than 2030 years required by reforestation.

Mountains as Water Guardians in a Warming Climate

The water crisis faced by Central Afghanistan is an interconnected issue within climate change, institutional breakdown, natural pressure, and deforestation. Though there is no single remedy available to cope with this comprehensive issue, mountain reforestation in Afghanistan is one adaptation measure that has a multifaceted benefit holistically: improving dry-season water access to rural communities, minimizing landslide danger, improving soil carbon stocks, and promoting rural economic development via sustainable forest resources and Payment for Ecosystem Services programs. To tap into this resource, there is an imperative to view policy change, garnering climate change finance internationally, community engagement, and mainstreaming within comprehensive water resource management. A holistically comprehensive understanding is required on how mountain regions can no longer serve as mere aesthetic backdrops but rather serve as Water Sentinels, and mountain restoration is equivalent to the very survival of Climate-Resilient Downstream Communities.

This article examines Indonesia’s transition from reactive emergency disaster spending...

This article examines the DRC–Rwanda peace accord through the lens...

This article offers a comparative reflection on how Islam has...

This article examines how youth-led, digitally networked movements are reshaping...

This article examines why forest-based approaches remain critical for addressing...

This article exposes the injustice of Afghanistan’s exclusion from COP30...

This article highlights the significant emotional and mental health burden...

This article defines Code Green as a model of public...

This article analyzes how China’s ambitious green transition serves not...

This article traces how the 2025 UN General Assembly turned...

This article looks at how Indonesia’s provinces with extensive biodiversity...

This article examines how climate change and privatization intersect to...

This article analyzes how Trump’s second time withdrawal from the...

This article critically analyses Pakistan’s worst floods ranging from the...

This article examines the climate vulnerabilities of Pari Island in...

This article traces how Pari Island in Jakarta’s Thousand Islands...

This article explores how ecotourism in Indonesia’s Thousand Islands generates...

This article compares how U.S. Presidents Joe Biden and Donald...

This article explores the devastating impact of human activities such...

This article critically examines the European Union’s Carbon Border Adjustment...

This article confronts the human and ecological cost of Indonesia’s...

This article examines the way in which the electric vehicle...

This article explores how Jakarta’s TransJakarta Bus Rapid Transit system...

The Indonesian government's PSN projects, particularly palm oil-based energy estates,...

Leave A Comment