On the first day of July 2025, Thailand’s Constitutional Court suspended Prime Minister Paetongtarn Shinawatra from office. The decision followed a petition by 36 conservative senators who accused her of ethical and constitutional violations over a phone conversation with Hun Sen, the former Prime Minister of Cambodia. To the casual observer, this may appear to be yet another routine legal controversy. But to those who understand the contours of power in Thailand, this incident reveals something deeper: a systemic regression of electoral democracy that has never been allowed to mature into a legitimate political order.

Paetongtarn is not merely a rising young leader; she is an unwelcome heir to Thailand’s entrenched political establishment. Her father, Thaksin, was ousted by the military in 2006. Her aunt, Yingluck, was removed by the judiciary in 2014. Now Paetongtarn, in a subtler yet equally ruthless fashion, has been sidelined by the Constitutional Court. In Thailand, elections are held, but their outcomes remain subject to unelected institutions that lack a democratic mandate. Democracy exists as a formality, not as the foundation of political authority.

What sets Paetongtarn’s episode apart from her family’s previous political tragedies is the overt interference of Hun Sen, a foreign actor within Thailand’s domestic affairs. As a former prime minister and current president of Cambodia’s Senate, Hun Sen not only leaked what should have been confidential diplomatic conversations, but also shaped public discourse and orchestrated the political fallout within Thailand. His actions cannot merely be read as provocation; they constitute direct interference in a neighbouring country’s internal affairs. Even more startling is that not a single Southeast Asian nation has unequivocally condemned this breach.

The silence of ASEAN member states is not born out of ignorance, but out of unwillingness. The principle of non-intervention, once held as the moral bedrock of the region, has now degenerated into a mechanism for evading responsibility. Every state knows that an intervention has occurred. Every government is aware that a norm has been brazenly violated. Yet none is willing to risk calling the violation by its name. Within such a structure, regional solidarity mutates into a system of collective impunity, where violations go unpunished and power operates unrestrained by ethical limits.

This reveals a double erosion, domestic and regional. In Thailand, the electoral authority is systematically neutered by institutions designed not to serve, but to filter. Courts, ethics commissions, and the military no longer act as guardians of the Constitution, but as enforcers of an untouchable oligarchy. At the regional level, collective mechanisms meant to uphold shared norms have lost their ability to distinguish between protecting sovereignty and condoning symbolic violence.

There is no neutrality in such circumstances. When an elected leader is deposed over a leaked diplomatic conversation, and the entire region refuses to take a position, what is at stake is not just the fate of a single figure, but the boundaries of the region’s political imagination. If a conversation can justify the annulment of electoral authority, then there is no longer a safe space for autonomous foreign policy. If words become weapons, then diplomacy itself ceases to exist.

Hun Sen understands this gap. He does not need to deploy troops or issue overt threats. He selectively manipulates information to achieve maximum political effect. He knows that Thailand’s institutions are primed to eliminate anyone deemed a threat to the status quo. He merely has to nudge, and the machinery of power takes care of the rest.

This is a new form of coup. There are no guns, no tanks, no shouts in the streets. What remains are institutions, procedures, and legal narratives. Such coups do not invite resistance because they wear the mask of legitimacy. And precisely because of this, they are far more dangerous. They are harder to detect, more difficult to resist, and nearly impossible to delegitimise. In many cases, resistance itself will be framed as an additional violation.

Paetongtarn is not confronting a single legal case. She is confronting a system meticulously designed to eliminate any figure who dares to offer a different possibility. This system functions not only domestically, but also in coordination with transnational actors who recognise that stability is no longer achieved through openness, but rather through the suppression of dissent. Southeast Asia is drifting not toward the abolition of democracy, but its neutralisation.

The crisis we now witness reveals that the death of ASEAN norms is not simply about the absence of response, it is about the transformation of those norms themselves. The principle of non-intervention, once devised as a buffer against postcolonial domination, has now become a shield for unaccountable power. Originally, it was intended to prevent one state from dominating another. Now, it is invoked to justify silence in the face of elite domination over their own populations. This represents a functional shift that is both ethically corrosive and structurally debilitating to the region’s democratic resilience.

ASEAN’s collective norms are often portrayed as the product of consensus-building. In reality, they have more frequently served as tools for avoiding accountability. When violations like those orchestrated by Hun Sen are met with inaction, it is not merely an institutional failure; it is a systemic failure. It is a shared decay, tacitly endorsed across the region. In this condition, the region’s primary force is no longer its major powers, but its pervasive minor fears: the fear of instability, the fear of political backlash, and most dangerously, the fear of imagining that the current order could be otherwise.

What Hun Sen has done also exposes a new dynamic in intra-ASEAN power relations. He is not merely a former leader clinging to relevance. He is a symbol of a political logic that transcends national boundaries. As a figure who has maintained power for over three decades, Hun Sen has mastered a crucial art: turning institutions into personal instruments. Today, this art is not only retained within Cambodia, it is projected across borders. By exploiting Thailand’s systemic vulnerabilities, he positions himself not as an outsider but as an organic part of a regional ecosystem of mutual reinforcement.

In this context, ASEAN’s failure is not a failure of action, it is a failure of imagination. Regional norms have ceased to constrain power and now serve as its new legitimacy. Beneath the surface of integration rhetoric lies a profound fragmentation of values. Member states restrain themselves not out of mutual respect, but out of habituated fear of disturbing the region’s fragile, illusory balance. This is mutual containment, not mutual respect.

If this trajectory continues unchallenged, it will not only be norms that die, but politics itself will become a hollow simulation. We will see more elections annulled by courts, more leaders removed by technocratic bodies, and more diplomatic conversations weaponised to destroy political alternatives. This is not a future that can be sustained. It is the beginning of a quiet, orderly, and lethal regional void.

We have seen how the procedure is used to strip away mandates. We have seen how courts are used to filter who may remain. And now, we are witnessing how diplomatic speech can be turned into an instrument of political assassination. All of this reveals that politics is not growing, it is being embalmed to appear alive, while already dead.

In such a moment, our choice is no longer between intervention and neutrality. It is between allowing the system to kill politics slowly, or confronting the logic of power that endlessly reproduces itself. Southeast Asia is not in crisis due to a lack of procedure, it is ailing because of a lack of courage to take a stand.

Paetongtarn may not be the solution to all the region’s problems. However, she serves as a reminder that power in this region has never been designed to accommodate change. And if this region cannot protect the people’s right to choose and to defend their choices, then it can no longer call itself a political community. It becomes merely a space governed by fear and sustained by collective silence.

What is lost today is not just a leader, it is the possibility of principled leadership. What is lost is the courage to say something has gone terribly wrong. If this continues, Southeast Asia will lose more than its legitimacy, it will lose its future as a region worthy of trust.

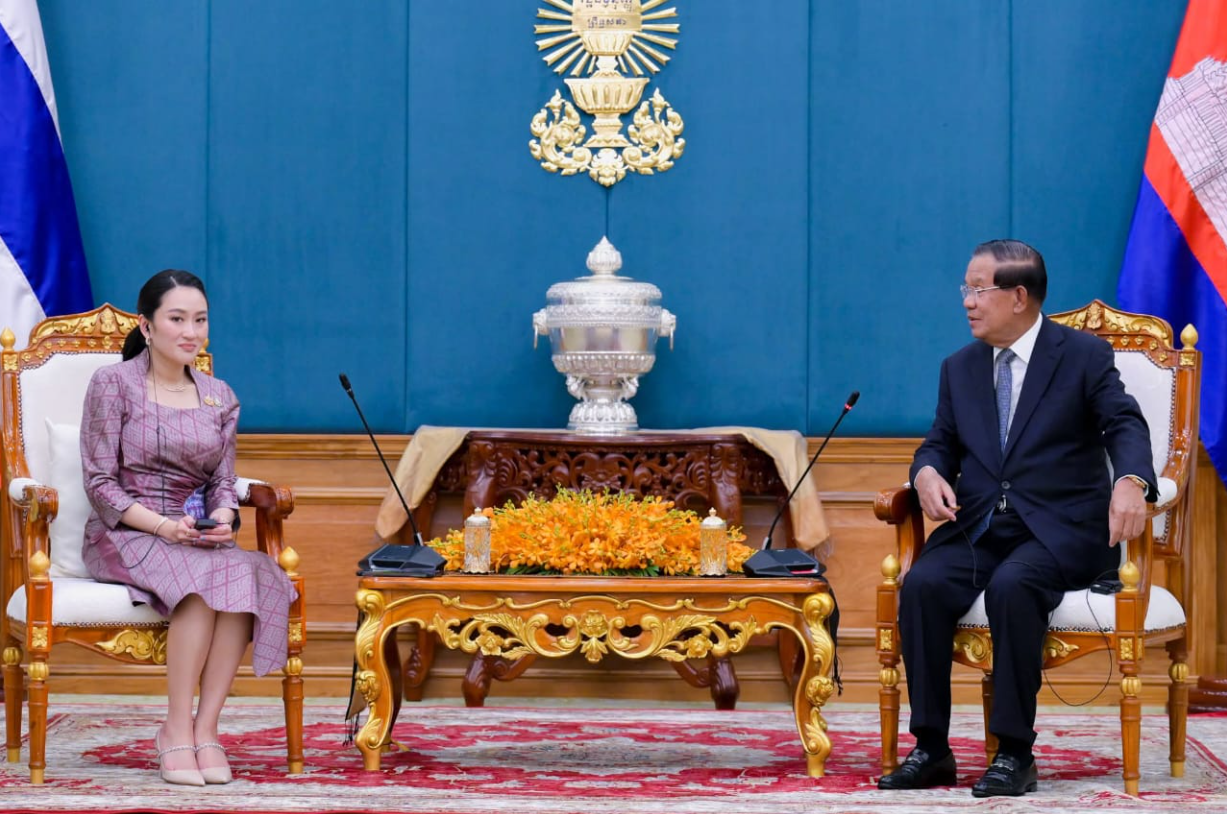

Note: On the cover image, Thai Prime Minister Paetongtarn Shinawatra with Cambodian Senate President Samdech Techo Hun Sen at the commemoration of the 75th anniversary of their diplomatic relations in April 2025. Source: The Nation

This article examines undersea cables as a critical yet vulnerable...

This article examines the Apple Developer Academy in South Sulawesi...

This article highlights the shifting global structure from a unipolar...

This article explores Gaza’s devastation as both a humanitarian tragedy...

This article examines how the UN Security Council’s veto power...

This article explores the concept of science diplomacy as a...

This article uncovers how the political ascent of Zohran Mamdani...

This article examines how the global silence over Sudan’s humanitarian...

This article examines the way artificial intelligence is transforming global...

This article reexamines the meaning of ASEAN neutrality in light...

This article analyzes the geopolitical and institutional significance of the...

This article examines how deepfakes have evolved from isolated digital...

This article critically examines the evolving contestation of the Responsibility...

This article contends that Trump’s high-value diplomacy in the Gulf...

This article examines how the EU-ASEAN partnership has significantly evolved...

This article examines how President Prabowo Subianto seeks to combine...

This article takes a look at how Prabowo’s UN address...

This article explores how Gulf states, particularly Saudi Arabia and...

This article examines Armenia’s blocked bid to join the Shanghai...

This article examines Indonesia’s recent acquisition of the Turkish-made KHAN...

This article explores how U.S. tariffs, intended to strengthen leverage...

This article explores how the OIC, despite its authority to...

This article examines how the 2025 recognition of Palestine by...

This article shows how the United States’ 19% tariff on...

Leave A Comment