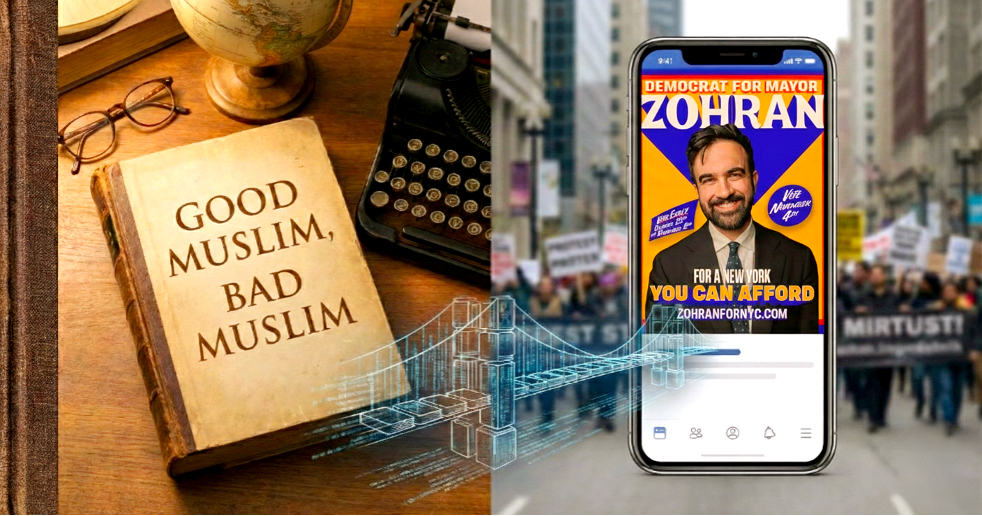

When Zohran Mamdani first started going viral on TikTok; his passionate oratory communications about housing justice, racial justice, and economic justice reaching millions, it seemed like a brand-new voice in politics had suddenly emerged. But there was something about his politics that sounded surprisingly familiar, specifically his use of discourse to denote not moral issues but structural issues. It was like the voice of a scholar that I had studied before. And then it clicked; that’s because Zohran Mamdani’s father is Mahmood Mamdani, who was born in Uganda but produced a vital book titled “Good Muslim, Bad Muslim: America, the Cold War, and the Roots of Terror”. The book fundamentally transformed how people around the globe understood Islam after 9/11.

Mahmood Mamdani’s book, published in 2004, , was thus an exercise in intellectual resistance. In the aftermath of September 11, Western discourse had constructed a binary contrast in Islamdom between "good Muslims," who conformed to global norms, and "bad Muslims," who resisted. In other words, "all Muslims are not terrorists." Mahmood Mamdani destroyed this binary contradiction. He pointed to the origin of political violence not in Islam but in the geopolitics of the Cold War, that is to say, in American efforts to militarize Islam in Afghanistan.

At a point when dissent was considered an act of betrayal, these thoughts were quite radical. “Mamdani encourages readers to think past moral condemnation to an understanding of how states perpetuate cycles of violence,” wrote Bilal Baloch. It challenged both scholars and decision-makers but remains to date one of the most influential approaches to understanding “the war on terror”:

In a popular online lecture, a Muslim scholar named Yasir Qadhi retraced topics explored within Mamdani’s thesis when he referred to the book "a work that reframes how we talk about Islam and politics." According to Qadhi’s observations, Good Muslim, Bad Muslim challenged international communities to reconsider moral typologies characterizing international foreign policy because instead of pursuing queries like “Why do Muslims hate us?”

Mamdani asked “What political systems produced these conflicts in the first place?”

But its contribution doesn’t lie there alone. Indeed, its transition, moral to historical, subjects to structures, was revolutionary. It unearthed how global hegemons used religion for political intentions whereas, simultaneously, denied responsibility for creating conditions to which they solved.

Fast forward two decades, and there’s a resurrection of Mahmood Mamdani’s thoughts in his son’s politics. Today’s assemblyman in New York State, and already the mayor-elect of New York City, embodies his father’s intellectual heritage. While his father deconstructed those narratives that create legitimacy for imperialist wars, his son deconstructs those systems that perpetuate inequality in cities.

In his campaign speeches, Zohran listens to no one who believes poverty is a product of individual failure. Rather, there’s history to point to; disinvestment, housing markets that prey on people’s vulnerability. As a leader, his model of behavior mirrors his father’s scholarship. Both are complicated to summarize. Both offer calls to confront structures, not to scapegoat.

The intellectual boldness of both Mamdani’s was informed by displacement. The Senior Mamdani was born in Bombay in 1946 to an Indian Muslim family and raised in Kampala , Uganda. He grew up amidst colonialism, nationalism, and dictatorship. He was expelled during Idi Amin’s regime. He re-established his academic life elsewhere to become one of the leading voices in postcolonial issues related to governance in Africa. The bravery to publish “Good Muslim, Bad Muslim” in a period in which there was great skepticism against Muslims emanated from his experience.

As such Zohran Mamdani comes from a politicized family surrounded by politics and art. He was raised between continents because his father was a political theorist, and his mother was renowned film-maker Mira Nair. He has been exposed to three continents; the Indian, Ugandan, and American, because his family has been between continents. He was politicized because his family environment politicized him.

The irony, however, is unmistakable. A platform famous for its trends and bite-sized chunks of info has revived, the voice of a thinker who made his reputation because nothing was ever simple for him. The interest in Zohran, through questions on is whether he is ‘good’ or ‘radical’ in politics? is itself a reflection of the same binary his father upended two decades ago, because in both instances, the public’s need to moralize prevails over what’s actually happening beneath its surface.

What Mahmood Mamdani (the father ) taught through his theory, Zohran (his son) does in practice; that moral dichotomies 'good Muslim, bad Muslim' or 'good mayor, bad mayor' is a distraction to deconstructing these destructive systems."

For those studying Islamic politics, “Good Muslim, Bad Muslim” continues to represent essential reading. The book spans disciplines to remind readers that Islam cannot ever be considered in terms that are not historical or political. The book’s methodological approach to considering readings between Empire, Violence, and Cultural Discourse provides crucial resources to contemporary debates around Islamophobia, Populism, or Global Inequality.

The inclusion of Mamdani’s writings in academic curricula would greatly enhance students’ comprehension of how “civilization” and “terror” narratives influence global politics. It illustrates how knowledge itself carries an agenda, that moral certitude sometimes begins with historical truth. A Legacy of Courage and Continuity but if Zohran Mamdani is mayor of New York City, it is not because of his status as a trend-setter or because of his youth. Rather, it represents the end result of an intellectual and moral tradition, which started with a thinker who was an opponent of empire but continues with a politician who opposes inequality.

This article uncovers how the political ascent of Zohran Mamdani...

This article examines how the global silence over Sudan’s humanitarian...

This article examines the way artificial intelligence is transforming global...

This article reexamines the meaning of ASEAN neutrality in light...

This article analyzes the geopolitical and institutional significance of the...

This article examines how deepfakes have evolved from isolated digital...

This article critically examines the evolving contestation of the Responsibility...

This article contends that Trump’s high-value diplomacy in the Gulf...

This article examines how the EU-ASEAN partnership has significantly evolved...

This article examines how President Prabowo Subianto seeks to combine...

This article takes a look at how Prabowo’s UN address...

This article explores how Gulf states, particularly Saudi Arabia and...

This article examines Armenia’s blocked bid to join the Shanghai...

This article examines Indonesia’s recent acquisition of the Turkish-made KHAN...

This article explores how U.S. tariffs, intended to strengthen leverage...

This article explores how the OIC, despite its authority to...

This article examines how the 2025 recognition of Palestine by...

This article shows how the United States’ 19% tariff on...

This article reflects on the Thailand–Cambodia border dispute, capturing it...

This article examines how the absence of coordinated trade negotiations...

This article explores the strategic implications of the Indonesia–Turkey defence...

This article reveals how Hungary, a country that is frequently...

This article examines how a leaked phone conversation between the...

This article examines the 2025 border crisis between Thailand and...

Leave A Comment